Source: WI-ID PDF

Categoria: Articolo

Romoli Ferrucci del tadda Expertise Ita Bacarelli

ROMOLO FERRUCCI DEL TADDA (Firenze, 1544 – 1621)

Il Villano per Livorno

Nel 1601 la Guardaroba del Granduca di Toscana dette in prestito due figurine in argento allo scultore e orefice Antonio Susini (1558-1624), probabilmente per eseguire delle copie in bronzo. Stando al relativo documento una delle statuette rappresentava un “Villano con cappello con bastoncino che s´appoggia in su il bastone”; l’altra è semplicemente chiamata “Pastorino” (1). Tutte e due le figurine di argento sono perdute ma il “Villano con cappello con bastoncino che s´appoggia in su il bastone” esiste in più versioni in bronzo, le migliori delle quali sono state ragionevolmente attribuite al Susini (2). Una versione del Villano (figure 2,4,6 e 8) nel Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia a Roma ha forti affinità con lo Zampognaro seduto (figura 9) in bronzo sempre nello stesso museo (3). Entrambi i due bronzetti condividono la stessa provenienza ed è perciò molto probabile che i due modelli siano stati in origine concepiti come pendants e che il Pastorino consegnato a Susini insieme al Villano di argento rappresentava uno Zampognaro seduto. Inoltre, una figura di bronzo “che sona la piva” è documentato come lavoro del Susini in un inventario mediceo del 1623 (4). Potrebbe essere la versione dorata preservata oggi al Museo Nazionale del Bargello a Firenze (5). Il Susini non era un artista creativo (6). Agli inizi del diciassettesimo secolo era ancora impiegato nella bottega del Giambologna, il grande scultore fiammingo alla corte dei Medici. Dal 1598 in poi il Susini comincia a produrre piccoli bronzi basati sui modelli del Giambologna. È perciò abbastanza probabile che le due figurine in argento date al Susini erano state disegnate dal suo maestro. Un´altra statuetta “di genere” in argento è documentata nelle collezioni medicee come opera del Giambologna. Essa rappresentava una Donna con oca. Fusa nel 1574, il suo modello è conosciuto da una sola versione in bronzo (7). Intorno a questo periodo si possono datare anche le due statuette perdute in argento del Villano e del Pastorino. Una tale datazione è confutata dalle seguenti considerazioni: nell´ottava decade del sedicesimo secolo il Giambologna stava lavorando alle sculture per il giardino della Villa di Pratolino, la residenza prediletta del Granduca Francesco, e Filippo Baldinucci ci dice che per quel giardino lo scultore fiammingo fece “in pietra alcune statue di villani” (8). E´ perciò non difficile immaginare che i modelli per il Pastorino e lo Zampognaro seduto siano da porre in relazione con queste sculture. Forse sono stati fusi direttamente dai modelli di contadini inventati dal Giambologna e ricordati dal Baldinucci (9). Nessuna di queste statue in pietra di contadini è sopravvissuta ed è impossibile sapere con certezza se Giambologna effettivamente ne scolpì. Baldinucci è l´unica fonte che le menziona ma lui si sbagliava spesso. Comunque, una statua rappresentante un Zampognaro seduto è documentata attraverso uno dei disegni che Giovanni Guerra ha fatto del giardino di Pratolino (10). E´ una versione molto simile al piccolo bronzo di Roma ed è perciò probabile che possa essere del Giambologna. Che il Giambologna abbia ideato almeno uno di questi modelli “di genere” è comunque fuori dubbio. Infatti il suo grande amico Benedetto Gondi possedeva una statuetta in bronzo rappresentante un “Pastorino” che nell´inventario del 1609 della sua importante collezione d´arte viene descritto come “di mano e l´originali del Cavaliere Gian Bologna” (11). Inoltre quando l´erede al trono di Inghilterra chiese alla corte medicea dei bronzetti tratti dai modelli del Giambologna, all´inizio del diciassettesimo secolo, un Pastorino con bastone e uno Zampognaro seduto furono mandati insieme ad altre statuette da modelli del Giambologna in Inghilterra (12). Nel documento doganale datato 1611 uno segue l´altro e questo conferma che queste due composizioni erano state in origine pensate come dei pendants (13). I bronzetti del Giambologna furono già usati come doni diplomatici dai Medici per le corti europee alla metà degli anni ottanta del Cinquecento (14). Quando Susini comincia a riprodurre i modelli del suo maestro in scala più vasta i bronzi tratti da modelli del Giambologna diventarono molto popolari e trovarono la loro strada anche in collezioni non aristocratiche. Come già riconosciuto da Hans Robert Weihrauch nel 1967, la diffusa popolarità che questi bronzetti ricevettero all´inizio del diciassettesimo secolo ebbe un’altra importante consequenza per la scultura europea. Bronzi tratti da modelli del Giambologna sono allora diventati modelli popolari per la statuaria da giardino specialmente al nord delle Alpi (15). Una composizione come quella dello Zampognaro seduto, inventata per decorare un giardino fiorentino, servì, per esempio, come modello per una statua che si trovava in una “grotta” nel cortile della casa di Rubens ad Anversa (16). D´altra parte nessun modello del Giambologna fu usato per statuaria da giardino in Toscana (17). Cercheremmo invano per modelli dal Giambologna tra le statue o gruppi “di genere” scolpiti per il giardino di Boboli durante il breve regno di Cosimo II (1609-1621) che fu responsabile per un revival di questo tipo di scultura (18). Per quanto som un modello del Giambologna fu certamente usato in Toscana solo una volta in scala maggiore (19) ma questo successe in un differente contesto, pubblico e commemorativo. Questa copia era una libera interpretazione dal “Villano” (figure 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, 11, 19, 21, 24, 26). Fu scolpita per una fontana di Livorno, il grande porto del Granducato di Toscana, da Romolo Ferrucci detto Del Tadda (1544-1621) membro della famosa famiglia di scultori di Fiesole, e figlio del famoso Francesco del Tadda, il primo a riscoprire i segreti per intagliare il porfido persi dopo l´antichità (20). La storia del “Villano” di Livorno è di grande interesse sia per come viene recepito il Giambologna in Italia, sia per gli studi sulla scultura Toscana del primo Seicento: Anthea Brook ne ha già parlato (21). Ma sia recenti studi sul Giambologna, sia gli studiosi di Romolo Ferrucci non hanno saputo notare la dipendenza di questa statua da un modello inventato dal Giambologna. Il “Villano” del Ferrucci è documentato visivamente già nel tardo Settecento. Nel 1937 Cesare Venturi pubblica un articolo monografico dove fa un sunto della storia della statua e della fontana su cui stava. Egli riproduce inoltre un disegno e un dipinto che confermano, al di là di ogni dubbio, che era basata su un modello del Giambologna (22): 1. il disegno (figura 12) è opera di Lorenzo Tommasi, un ingegnere della fine del Settecento, e raffigura un pastore in piedi in una posa molto simile al bronzo del Giambologna (23). Alla sua destra si staglia un cane che non sembra in relazione con la statua. 2. il dipinto (figura 13) è stato attribuito a Giuseppe Maria Terreni (1739-1811) ed è conservato nel Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori a Livorno. Riproduce un Villano con cane su una base rettangolare. Nel dipinto l´animale è rappresentato più vicino al Villano rispetto al disegno, è rappresentato a tre quarti e guarda verso la sua destra(24). Nulla si conosce della storia di questa tela. Al contrario, del disegno sappiamo che fu commissionato da Mariano Santelli per illustrare la sua ben conosciuta storia di Livorno, Stato antico e moderno ovvero origine di Livorno uscito in tre volumi a Livorno tra il 1769 e il 1762 (25). Il disegno è posto però tra le pagine 197 e 198 del quarto tomo della Storia del Santelli, rimasto manoscritto (26). Nè il disegno, né il dipinto erano ovviamente ideati come rappresentazioni accurate del gruppo scultoreo. Il disegno è molto sommario. E nel dipinto ambe le figure sono colorate in evidente contraddizione con l´aspetto originale delle due statue. Al tempo in cui il disegno e il dipinto furono eseguiti, la statua del Villano non era più al suo posto sulla fontana. Di fatti sappiamo che nel 1737 Giovan Filippo Tanzi, uno scultore di Carrara, propose di scolpire una statua per rimpiazzare l´originale (27). Come specifica il Santelli, soltanto la statua del cane rimaneva sulla fontana quando lui scriveva la sua Storia. Il Santelli aveva commissionato il disegno dal Tommasi per cercare di documentare come appariva in origine il gruppo scultoreo del Ferrucci, soprattutto a beneficio dei “dilettanti del disegno, della scultura, come ancora dell´Antichità” (figura 15) (28). Il Santelli inoltre ci dice che riuscì (“mi è riuscito”) ad ottenere questo disegno (29). Questo fa suppore che egli conosceva l´ubicazione del Villano e che non fosse semplice averne il disegno. E´ però ugualmente possibile che lui si sia rifatto ad un modello visivo precedente, ma a noi oggi perso. Il Santelli aggiunge che il disegno avrebbe confutato alcune informazioni sbagliate precedentemente pubblicate (30). Si riferisce innanzitutto a coloro che avevano erroneamente identificato una testa di marmo inserita in un muro di Via S. Giovanni a Livorno come frammento della “statua del Villano” (31). In seguito, il Santelli usa il disegno come prova contro la tesi che il Villano sarebbe stato in origine tra due figure di cani. Il disegno provavava che questa affermazione era falsa: il gruppo era composto dalla statua del Villano e di quella di un solo cane. Questa informazione sbagliata era stata affermata da Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti nel 1768 (32), il quale si basava su un manoscritto che si trovava allora nella biblioteca Magliabecchiana, ma che oggi è custodito nella Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze (33). È in questo manoscritto che si trova anche l´informazione sulla paternità delle sculture. Questo manoscritto era proprietà di Anton Francesco Marmi (1665-1736) (34). È composto da informazioni su vari artisti e opere d´arte e include una sezione intitolata “Notizie di Livorno”. Secondo queste inedite “Notizie” che non è possibile datare con precisione: “V´è la Fontana antica detta del Villano per esservi una statua di Macigno ammezzo a due cani, opera buona di Romolo del Tadda” (35). Secondo il compilatore di queste “Notizie” il Villano del Ferrucci era di macigno, un tipo di pietra arenaria dura, dalle tonalità grigio bluastre. Comunque il Santelli è critico anche su questo punto. Egli scrive infatti che un bastione della fortezza di Livorno era denominato “del Villano”: “da una statua di macigno, o di marmo che fosse, rappresentante un Contadino all´uso di quèi tempi quale appoggiasi ad un legno fissato nel terreno con un sacco fra le mani ed un barilozzo pendente, ed un cane sedente alla sinistra di se medesimo tutto diverso da ciò che ne scrisse un manoscritto della Magliabecchiana Pubblica Biblioteca” (figura 16) (36). Nonostante quasi tutte le statue del Ferrucci fossero di pietra arenaria, egli era capace di scolpire qualsiasi tipo di marmo, avendo imparato l´arte dal padre Francesco che era capace di intagliare la più dura delle pietre, il porfido (37). Ma il Santelli aveva un´altra ragione per dubitare delle informazioni dateci dal manoscritto delle “Notizie di Livorno” e concernenti il materiale del gruppo statuario di Livorno. Infatti, quando lui scriveva la sua Storia nel tardo Settecento, il cane era ancora esistente e lui poteva ancora vedere con i suoi propri occhi che era di marmo (38). Inoltre, anche il Venturi indica che il gruppo fosse fatto in marmo, perché ricordava di aver visto nella sua gioventù che la sua base rettangolare era di marmo (39). Era invece il piedistallo (la fontana vera e propria) a essere fatta di pietra e questo può aver suggerito erroneamente all´autore delle sopra menzionate “Notizie di Livorno” che anche le sculture erano “di macigno”. Le due sculture del Ferrucci per Livorno, erano come vedremo in seguito più in particolare, un gruppo di commemorazione pubblica. Sarebbe stato per ciò difficile immaginare che potessero essere di un materiale diverso dal marmo di Carrara, di cui in effetti il Villano consiste. Sfortunatamente l´autore delle “Notizie di Livorno” non ci rivela la data in cui fu commissionato il gruppo del Ferrucci. È stato suggerito che la commissione risale al 1605 (40). Tuttavia, questo non è possibile: il Santelli semplicemente parla di questo gruppo nel contesto degli avvenimenti del 1605 (41). Dall’altro canto, il Santelli offre un “terminus ante quem” per la sua esecuzione: la data in cui la statua fu posta sul piedistallo che funzionava anche come fontana. Secondo un passaggio successivo nel manoscritto del Santelli questo occorse nel 1628: “si leva la fonte del Villano, di cui si parlò all´anno 1605 dal luogo, ove fu nei opprimi tempi, cioè sotto il Bastione suddetto, e si porta sulla piazza detta già dei cavoli in faccia alla presente macelleria della mala carne, ove ancor si pose sopra del piedistallo, che era il getto di detta fonte la statua del Villano” (figura 18) (42). Secondo il Santelli, questo piedistallo fu costruito da un certo maestro Bernardo Betti da Pistoia, su cui non ho potuto trovare alcuna informazione (43). Nel 1628 perciò dette statue erano completate. Ma siccome Romolo Ferrucci morì nel 1621, devono essere per forza datate prima della sua morte. La più probabile ragione per questa commissione fu l´inaugurazione dell´acquedotto di Livorno. Secondo Nicola Magri l´acquedotto fu completato nel 1607 (44). Nel suo “Discorso sopra ai condotti e le fogne di Livorno”, un manoscritto compilato durante il regno di Cosimo III, Lorenzo Fallera sostiene invece che detto acquedotto fu completato nell´anno 1612 (45). Una datazione tra il 1607 e il 1612 appare perciò il più probabile “terminus post quem” per quella che doveva essere una commissione ufficiale, avvenuta o ancora negli ultimi anni del regno di Ferdinando I (1587-1609), sotto il quale grande fu lo sviluppo di Livorno, o sotto il regno del figlio Cosimo II per cui lo scultore lavorò, come vedremo, scolpendo statue per i giardini di Boboli. La più antica traccia della fontana è inclusa in una pianta di Livorno, la “Pianta del condotto che porta l´acqua alle fonti pubbliche della città e porto di Livorno et in altri vari luoghi della medesima” di Giuseppe Ruggieri che data dal 1757. Si trova in una collezione privata ma fu pubblicata da Renzo Mazzanti e Luciano Trumpy nel 1987 (46) Lì vediamo la fontana vicino alla darsena sotto il numero 59. È qui dove fu posta nel 1628 e dove il Santelli la descrive nel 1772: “al presente la detta fonte è sulla cantonata della nuova stradina, che dalla malacarne conduce alla pescheria vecchia…, e fa facciata in piazza detta dei cavoli, e fu ivi posta del 1628 da Maestro Bernardo Betti muratore fatti che furono i casamenti dell´una e dell´altra parte di detta stradina l´anno 1628” (47). Il piedistallo è visibile in tre riproduzioni di dipinti e in due vecchie fotografie pubblicate dal Venturi (48). Ma non è chiaro dove la fontana si trovasse prima del 1628. Come abbiamo visto, il Santelli dichiara che la fontana era posta sotto il bastione, detto del Villano (49). Tale bastione fu costruito nel 1496 dal popolo della campagna intorno a Livorno che lo difese l´anno seguente durante l´assedio della città da parte dell´imperatore Massimiliano I (50). Per onorare il popolo delle campagne livornesi, il comandante fiorentino della città eresse una fontana sotto il bastione e vi pose sopra, secondo il Magri, una statua di un contadino con cane accanto, a testimoniare la fedeltà dei contadini livornesi alla repubblica fiorentina (51). “Chi fosse Romolo del Tadda scultore di quei tempi non ho saputo trovarlo” scrive il Santelli e aggiunge di aver trovato un Romolo del Tadda attivo durante i regni di Cosimo I e Francesco I de’ Medici, riferendosi al Vasari e al Baldinucci: “ma questo è troppo lontano da tali tempi. Forse sarà sbagliato il nome. Chiarificheranno ciò i dotti illustratori presenti della nuova edizione del Baldinucci” (52). Inoltre, è molto improbabile che la Repubblica fiorentina ergesse un monumento alla memoria dei villici livornesi. Con ogni probabilità solo la fontana fu commissionata e prese il nome dal vicino bastione che faceva parte della vecchia fortezza. In seguito alla distruzione del bastione la fontana fu spostata mantenendo il suo nome originale e il gruppo statuario del Ferrucci rendeva chiara questa connessione. Più ricerca è necessaria per ricostruire la storia della fontana ma ciò è reso difficile dal fatto che pochi dati di archivio riguardanti le fortificazioni e la pianificazione urbana di Livorno sono arrivate fino a noi. Romolo Ferrucci del Tadda era nato in una famiglia di scultori di Fiesole il 29 settembre 1544 e fu tenuto a battesimo da Niccolò Tribolo il giorno seguente (53). Sandro Bellesi ha stabilito che fu istruito dal padre Francesco che assistette nello scolpire la Giustizia di porfido che Bartolomeo Ammannati ideò per coronare la colossale colonna che ancor si erge in Piazza Santa Trinita. Cominciata nel 1569 quando Romolo aveva 25 anni, fu completata nel 1581. Negli anni 70 del Cinquecento Romolo che ancora lavorava per il padre, eseguì la tomba per l´Arcivescovo Giovan Battista Ricasoli in Santa Maria Novella composta di marmi misti. Appare come un artista indipendente dopo la morte del padre nel 1585. Tre anni più tardi lo troviamo al lavoro a Pisa e questo ci può suggerire una qualche relazione con Livorno. Secondo una lettera scritta da Traiano Bobba a Firenze a Marcello Donati, consigliere del duca di Mantova, datata 10 aprile 1590 Romolo, avrebbe fatto le grotte per i giardini di Pratolino e Pitti al tempo del Gran Duca Francesco (54). Sarebbe stato perciò a conoscenza dei lavori del Giambologna fatti per la Villa di Pratolino negli anni 70 del Cinquecento. Verso la fine del Cinquecento la statuaria da giardino diventò la specialità del Ferrucci. Infatti, ad eccezione del Villano, tutti i lavori del Ferrucci dagli anni 90 in poi sono sculture da giardino. Divenne inoltre uno specialista nello scolpire cani al punto tale che noi quasi ci aspettiamo che ogni cane (figura 14) del periodo sia di sua mano (55). L´inclusione di un cane nel gruppo statuario per la fontana di Livorno è perciò una specie di sua firma. Come scultore animalista il Ferrucci fu ricercato anche al di fuori dei confini della Toscana. Egli scolpì animali in pietra per la decorazione della fontana nel palazzo Gondi a Parigi, e per il duca di Mantova, per cui è detto avesse eseguito sette animali in pietra bigia prima del 1602. Altro “genere” in cui l´artista era specializzato era quello degli stemmi araldici. Il suo stemma decorava la facciata del palazzo in cui viveva e lavorava in Via S. Egidio al n. 6 (vedi retro copertina), da lui acquistato probabilmente nel 1604 e situato presso la bottega e la casa del Giambologna in Borgo Pinti (56). Col progredire della sua carriera, egli crebbe nella gerarchia dell´Accademia del Disegno, ovvero l´Accademia artistica Fiorentina. Dalla seconda decade del XVII secolo in poi, il Ferrucci lavorò soprattutto per i giardini di Boboli al servizio del Gran Duca Cosimo II. Secondo il Baldinucci scolpì il gruppo detto “del Sacco mazzone” secondo un modello di Orazio Mochi (57). Francesco Inghirami gli attribuisce inoltre a ragione tre grandi versioni scultoree tratte dai Caramogi di Jaques Callot (58).Tutte queste sculture erano in pietra arenaria e fatte tra il 1617 e la morte del Ferrucci avvenuta nel 1621. Ed è con queste statue del Boboli che il Villano condivide una serie di significanti punti di comparazione che confermerebbero la sua attribuzione allo stesso Ferrucci anche non sapendo nulla sulla commissione del gruppo scultoreo di Livorno. Nel Villano di bronzo ideato dal Giambologna la figura è in riposo e sembra meditare (figura 18). D´altra parte il Villano del Ferrucci ha la bocca aperta e gli occhi quasi al di fuori delle orbite come in un espressione di angoscia (figura 19). Tale espressione è da considerarsi totalmente aliena allo stile del Giambologna ma con forti punti di comparazione con le statue autografe del Ferrucci poste nei giardini di Boboli (il Saccomazzone e i Caramogi) (figura 20). In particolare, gli occhi del Villano ci ricordano quelli del Caramogio di destra (figura 20) che sono ancora più espressivi visto che la figura dipende da Callot. Simile al sopracitato Caramogio è anche il disegno degli orecchi (figura 20) e il modellato dei capelli del Villano. I capelli (figura 21) condividono affinità anche con le due figure del gruppo del Saccomazzone (figure 22 e 23). Infine, nelle statue del Ferrucci a Boboli troviamo delle striature (figura 25) sui vestiti e sugli stivali del Villano (figure 24 e 26) striature del tutto assenti nei modelli ispirati dal Giambologna e che ci testimoniano, nella loro esemplare perfezione di linea, l´abilità del Ferrucci nello scolpire. Per quanto riguarda l´abbigliamento del Villano vi è un altro significante punto di comparazione: il disegno delle scarpe (figura 26) corrisponde in tutto e per tutto alle scarpe nelle statue del Ferrucci a Boboli (figura 27). Il Villano del Ferrucci non è una copia servile del Giambologna. Nonostante il marmo rispetti la posa generale del piccolo bronzo di Roma, il Ferrucci ci offre una totale reinterpretazione di questo prototipo. La principale differenza risiede, come abbiamo visto, nella testa. Nel marmo la testa è energicamente volta verso l´alto. L´apertura della bocca può essere probabilmente spiegata da questa modifica come espressione connessa a o risultante da questo movimento. Ad ogni modo la differente posizione della testa e dell´apertura della bocca sono da mettere in relazione al carattere commemorativo della statua. Ci sono inoltre altre piccole differenze. Per esempio, la posizione del piccolo barilotto ci indica che il Ferrucci ha ripensato questa composizione in termini di un grande gruppo di marmo. Nella statua di marmo l´assenza dello ‘zaino’, presente nel bronzetto contribuisce ad alleggerire la grande statua. Il Ferrucci ha anche cambiato il disegno dei vestiti. Non appaiono più le pieghe angolari come nel piccolo bronzo del Susini. Il Villano del Ferrucci è un capolavoro di tecnica scultorea. Dove la maggior parte dei dettagli nelle statue del Ferrucci di Boboli hanno perso la loro originale freschezza il Villano preserva tutti i delicati passaggi scultori come ci dimostrano le due mani in cui la maggior parte delle dita sono a tutto tondo. Ferrucci non era un genio inventivo, ma come Antonio Susini assistente nel Giambologna nella produzione dei piccoli bronzi, egli fu capace di ripensare le composizioni del suo grande maestro in maniera originale. E come il Susini aveva il dono per una squisita rifinitura. La riscoperta del Villano aggiunge considerevolmente alla nostra conoscenza dell´impatto che il Giambologna ebbe sugli scultori contemporanei e ci fa riconsiderare la posizione del Ferrucci nella storia della scultura fiorentina degli inizi del diciassettesimo secolo. È da sperare che ci porti a nuove valutazione i sulla sua personalità e sulla sua produzione artistica.

Romolo Ferrucci del Tadda

ROMOLO FERRUCCI DEL TADDA

(Florence 1544 – Florence 1621)

The Villano for Livorno

In 1601, the Guardaroba, the household administration of the Medici grand dukes of Tuscany lent two silver figurines to the goldsmith Antonio Susini (1558-1624), by all likelihood for copying them in bronze. According to the relevant archival record, one statuette represented a «Villano con capello con bastoncino che s’appogia in su il bastone», or a «Peasant with hat and staff resting on his staff»; the other is called simply a «Pastorino», or «Small Shepherd».

Both silver figurines are lost, but the small «Peasant with hat and staff, resting on the staff» exists in several bronze versions, the best of which have been reasonably attributed to Susini.

A version of the Peasant (figs *) in the Museo Nazionale del Palazzo di Venezia in Rome has affinities with a Seated Bagpiper (fig. *) in the same museum. Both share a common provenance and it is therefore likely that the two models had been originally conceived as pendants and that the silver «Pastorino» handed over to Susini together with the silver Peasant represented a Seated Bagpiper. A bronze figure «che sona la piva» («that plays the bagpipe») is, moreover, documented as Susini’s work in a 1623 Medici inventory. It could be the gilt version preserved today in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence.

Susini was not an inventive artist. At the turn of the 17th century he was still employed by Giambologna, the great Flemish-born court sculptor of the Medici. From 1598 on Susini began producing small bronzes based on the models of Giambologna. It is therefore safe to assume that the two silver figurines consigned to Susini had been designed by his master.

Another silver ‹genre› statuette is indeed documented in the Medici collections as a work invented by Giambologna. It represented a Girl with a Duck: cast in 1574, its model is known from a single bronze version. From around that time would date also the two lost silver statuettes of the «Villano» and the «Pastorino».

Such a dating is supported by the following considerations. In the eighth decade of the sixteenth century Giambologna was working on the sculptural decoration of the garden surrounding the villa of Pratolino, the preferred residence of Grand Duke Francesco and Fillipo Baldinucci says that for that garden the Flemish sculptor carved statues of «peasants in stone». It is therefore not hard to imagine that the models for the Standing Shepherd and the Seated Bagpiper were related to this project.

Perhaps they were cast directly after the small models Giambologna invented for the statues of paesants referred to by Baldinucci.

None of the latter survives nor is it possible to ascertain beyond doubt that he did carve such statues. Baldinucci is the only source mentioning them, but he was often mistaken. However, a statue representing a Seated Bagpiper is documented through one of Giovanni Guerra’s drawings of Pratolino. It is of a very similar composition to the type of the small bronze in Rome and could therefore have been by Giambologna.

That Giambologna did make at least one model for a ‹genre› figure is, however, beyond doubt. Indeed, his great friend Benedetto Gondi owned a bronze statuette of a «pastorino» expressly said to be – in the 1609 inventory of his distinguished art collection – «by the hand and the originals of Cavaliere Gian Bologna».

Moreover, when the Heir Apparent to the British throne asked the Medici court for bronzes reproducing Giambologna’s models, a Seated Bagpiper and a Standing Shepherd were sent together with other statuettes after Giambologna models to England. In the bill of lading that dates from 1611 they follow one upon another and this further suggests that these two compositions had been originally conceived as pendants.

Small bronzes by Giambologna were first sent as diplomatic gifts by the Medici to European courts already in the second half of the 1580s. After Susini began reproducing the models of his master at a larger scale, ‹Giambologna bronzes› became more popular and found their way also into non-aristocratic collections.

As was recognized by Hans Robert Weihrauch already in 196*, the widespread popularity such bronzes began to enjoy in the early 17th century had another far-reaching consequence for European sculpture: ‹Giambologna bronzes› were now used as models for garden statuary, especially north of the Alps.

A composition such as that of the Seated Bagpiper, invented to adorn a Florentine garden, served for a statue of this subject that stood in a grotto in the courtyard of the house of Rubens in Antwerp.

Conversely, no Giambologna models were used for garden statuary in Tuscany. We would look, for instance, in vain for copies after Giambologna among the many ‹genre› statues or groups carved for the Boboli gardens in the short reign of Cosimo II (reigned 1609-1621) who was responsible for a revival of this type of sculpture.

As far as I see, a Giambologna model for small statuary was certainly copied in Tuscany only once in large scale. But this happened in a different, commemorative and public context.

This copy was a free interpretation of the «Villano», or Standing Paesant. It was carved for a fountain in Livorno, the busy port of Tuscany, by Romolo Ferrucci, called ‹del Tadda› (1544-1621), a member of a famous family of sculptors from Fiesole, and son of Francesco del Tacca, the first to re-discover the secret of tempering porphyry after Antiquity.

The story of the Livorno «Villano» is of great interest both for the reception of Giambologna in Italy and for the study of early 17th-century Tuscan sculpture. Anthea Brook has already referred to it. It was nevertheless overlooked in recent Giambologna studies nor have scholars of Romolo Ferrucci noticed the dependency of this statue from a model invented by Giambologna.

Ferrucci’s Villano is documented visually already in the later eighteenth century. In 1937, Cesare Venturi published a monographic article where he summarized its story and that of the fountain on which it stood. He also reproduced a drawing and a painting that confirm beyond doubt that it was based on Giambologna:

1. The drawing (fig.*) is by the late 18th-century engineer Lorenzo Tommasi and shows a Shepherd standing in a pose very similar to that of the Giambologna bronze. To his right is a dog that faces the viewer but does not seem to be related to the statue.

2. The painting (fig.*) has been attributed to Giuseppe Maria Terreni (1739-1811) and is preserved in the Museo Civico Giovanni Fattori at Livorno. It shows the Shepherd and the dog on a rectangular base. In the painting the animal stands closer to the «Villano» than in the drawing and is represented in three-quarters view looking to its right.

Nothing is known about the history of this canvas. On the contrary, the drawing was commissioned by Mariano Santelli to illustrate his well-known history of Livorno: Stato antico e moderno, ovvero origine di Livorno, 3 volumes of which appeared in Livorno between 1769 and 1772). However, the drawing is bound between folios 197 and 198 in the fourth, unpublished tome of Santelli’s Storia.

Neither the drawing nor the painting were obviously meant to be accurate representations of what appears to have been a sculptural group composed of the «Villano» and of the sculpture representing a dog. The drawing is very summary. And in the painting both figures are coloured – in evident contradiction to what the original statues would have looked like.

By the time the drawing and the painting were executed, the statue of the Peasant was not anymore standing on the fountain. Indeed, in 1737 Giovan Filippo Tanzi, a sculptor from Carrara proposed to carve a replacement figure.

As Santelli specifies, only the dog stood atop the fountain when he was writing his Storia. He had commissioned the drawing from Tommasi in order to document the original appearance of Ferrucci’s sculptural group, for the benefit of the «dilettanti del disegno, della scultura, come ancora dell’Antichità», «the lovers of the arts of disegno, sculpture and Antiquity» (fig.*).

Santelli says that he «managed» («mi è riuscito») to obtain the drawing. The use of this term implies that Santelli knew of the whereabouts of the «Villano» and that it was somehow complicated to have a drawing made of it. It is, however, equally possible that he had to resort to an earlier visual source that is lost to us.

Santelli adds that the drawing will confound some previously published wrong information. First, he refers to those who had erroneously claimed that a marble head inserted in the wall of via San Giovanni in Livorno was a fragment of the «Statua del Villano».

He then uses the drawing as a proof against

the claim that the «Villano» had stood originally between two dogs. The drawing proved this to be wrong: the group was composed by the statue of the Peasant and of that of only one dog.

Such a claim had been put forward by Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti in 1768. It was based on a manuscript then in the Biblioteca Magliabecchiana which is preserved today in the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence.

It is in this manuscript that the information on the authorship of the sculptures is contained. The manuscript had belonged to Anton Francesco Marmi. It is composed of information on various artists and works of art including a set of unpublished Notizie di Livorno, or Notes on Livorno. According to these undated and unpublished Notes:

v’è la Fontana antica detta del Villano per esservi una statua di Macigno a mezzo a due cani, opera buona di Romolo del Tadda.

For the compiler of the Notizie, Ferrucci’s Villano was made of macigno, a type of hard, blue-grey sandstone. However, Santelli is equally critical about this. He writes that a bastion of the fortress of Livorno was called «del Villano»:

da una Statua di Macigno, o di marmo che fosse, rappresentante un Contadino vestito all’uso di que’ tempi quale appoggiasi ad un legno fissato nel terreno con un sacco fra le mani ed un barilozzo pendente, ed un cane sedente alla sinistra di se medesimo tutto diverso da ciò che ne scrisse un manoscritto della Magliabecchiana Pubblica Biblioteca.

Indeed, no sculptures by Ferrucci in macigno have come down to us. Most of his statuary is in pietra bigia, but he was capable of carving any type of marble, since he learned his trade from his father Francesco who was able to cut hardest of all stones, porphyry.

However, Santelli had another reason for doubting the information provided by the manuscript Notizie di Livorno and concerning the material of the sculptural group in Livorno. Indeed, when he was writing his Storia in the late 18th century the dog was still extant and he could see with his own eyes that it was made of marble.

Also Venturi argues that the group was made of marble because he remembered having seen in his youth that the rectangular base or plinth on which it had stood was made of marble. It was this pedestal, or proper fountain, that consisted of stone, which could of course have caused the author of the above-mentioned manuscript Notizie di Livorno to assert that also the sculptures were «di macigno».

The sculptures Ferrucci carved for Livorno were as we shall see a public commemorative group. As such it could have hardly been made of a material other than Carrara marble and indeed this is the stone of which the Villano has been carved.

Unfortunately the author of the Notizie di Livorno does not reveal the date of the commission of the group to Ferrucci. It has been suggested to date it in 1605. However, this is not possible: Santelli only discusses them under that year.

Conversely, he offers a terminus ante quem

for its execution: the date of its placement of the statue on that pedestal that functions as a fountain. According to a later passage in Santelli’s manuscript volume, this occurred in 1628:

Si leva la Fonte del Villano, di cui si parlò all’anno 1605, dal luogo, ove fù ne primi tempi, cioè sotto il bastione suddetto, e si porta sulla piazza detta già de Cavoli in faccia alla presente Macelleria della mala carne, ove ancor si pose sopra del Piedestallo, che era il getto di detta Fonte la statua del Villano.

According to Santelli, this pedestal was constructed by a certain «Maestro Bernardo Betti da Pistoia», on whom I could find no information. By 1628 therefore the statues were completed.

But since Romolo Ferrucci died in 1621 they must date before his death. The most likely reason for their commission is the inauguration of the acqueduct of Livorno. According to Niccola Magri, the acqueduct was finished in 1607. Lorenzo Fallera’s Discorso sopra i condotti e le fogne di Livorno, a manuscript compiled during the reign of Cosimo III, argues instead for the year 1612.

A dating between 1607 and 1612 appears therefore to be the most likely terminus post quem for what must have been an official commission, either still by Ferdinando I, to whose energy the expansion of Livorno was due, or by his son Cosimo II, for whom the sculptor worked, as we shall see, carving statues for the Boboli gardens.

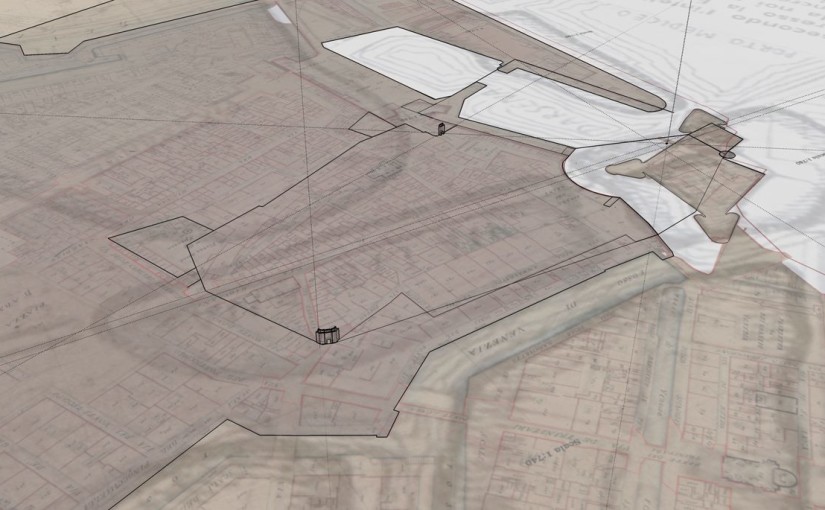

The oldest certain record of the fountain is included in a plan of Livorno, Giuseppe Ruggieri’s Pianta del condotto che porta l’acqua alle fonti pubbliche della città e porto di Livorno et in altri varii luoghi della medesima. This dates from 1757 and is in a private collection, but was published by Renzo Mazzanti and Luciano Trumpy in 1987. There we see the fountain close to the Darsena under no 59. And this is where it ws placed in 1628 and where Santelli still describes it:

Al presente la detta fonte è sulla cantonata della nuova stradina, che dalla malacarne conduce alla Pescherìa vecchia …, e fa facciata in Piazza detta de Cavoli, e fu ivi posta del 1628 da Maestro Bernardo Betti Muratore fatti che furono i Casamenti dall’una e dall’altra parte di detta stradina l’anno 1628.

The pedestal is seen in three reproductions of paintings and in two old photographs published by Venturi. But where the group stood before 1628 is not clear.

As we have seen, Santelli states that the fountain was located under the bastion, called «del Villano» . This bastion was constructed in 1496 by the countryfolk of Livorno who defended it during the siege of the city one year later by Maximilian, King of the Romans, the future Emperor Maximilian I.

To honour those Livornese peasents, the city’s Florentine commander erected a fountain under the bastion and placed, according to Magri, a statue of a Peasant atop, a dog standing by his side, in order to testify the countryfolk’s fidelity to the Florentine Republic.

However, already Santelli noted the discrepancy between the alleged date of the fountain’s erection and the biographical dates of Romolo Ferruci:

«Chi fosse Romolo del Tadda Scultore di que tempi non hò Saputo trovarlo», writes Santelli, and adds that he found a Romolo del Tadda active during the reigns of Cosimo I and Francesco referring to Vasari and Baldinucci: «ma questo è troppo lontano da tali tempi. Forse sarà sbagliato il nome. Chiarificheranno ciò i dotti Illustratori presenti della nuova edizione del Baldinucci».

Moreover, it is very improbable that the Florentine Republic would have erected a monument to the countryfolk of Livorno. By all likelihood only a fountain was commissioned and this took its name from the nearby bastion which was part of the old fortress. Following the destruction of the bastion, the fountain was moved nearby without losing its name and Ferrucci’s statuary group made the connection to its origin clear.

More research is needed to reconstruct the history of the fountain but this is difficult since very few archival records pertaining to the fortification and urban planning of Livorno have come down to us.

*

Romolo Ferrucci del Tadda was born into a family of sculptors from Fiesole on 29 September 1544 and was baptized by no less a godfather than Niccolò Tribolo the following day.

Sandro Bellesi has established that he was trained by his father Francesco whom he assisted in carving the porphyry Justice that Bartolomeo Ammannati had designed to crown the colossal column that stands on Piazza Santa Trinita. Begun in 1569 when Romolo was twenty-five it was completed in 1581.

In the 1570s, Romolo – working still with his father – executed the tomb of the bishop Giovan Battista Ricasoli in Santa Maria Novella composed of many different types of marble.

He appears as an independent artist after the death of his father in 1585. Three years later we find him working in Pisa and this suggests some kind of connection with Livorno.

However, according to a letter written by Traiano Bobba from Florence to Marcello Donati, advisor to the duke of Mantua, on 10 April 1590, Romolo had made the grottos of Pratolino and Pitti at the time of grand duke Francesco. He would therefore have been familiar with Giambologna and his work for Pratolino in the 1570s.

Towards the end of the Cinquecento, garden statuary became Ferrucci’s speciality. Indeed with the exception of the Peasant for Livorno, Ferrucci’s works from the late 1590s on are garden sculptures. He also became a dog specialist and we almost expect every dog (fig.*) of the period to be by him. The inclusion of a dog in the statuary group for the Fontana del Villano in Livorno is a kind of signature.

As an animalier, Ferrucci was sought for also outside Tuscany. He carved stone animals for the decoration of a fountain in the Gondi palace in Paris and for the duke of Mantua for whom he is said to have executed seven animals in pietra bigia before 1602.

Another ‹genre› in which he specialised was coat of arms and we can present here his own coat of arms (fig. *) decorating the façade of the building where he lived and worked in the via Sant’Egidio, acquired probably in 1604 and situated close to the workshop and house of Giambologna in Borgo Pinti.

As his activity prospered, he rose in the hierarchy of the Academia del Disegno, the Florentine artistic academy.

From the second decade of the 17th century on, Ferrucci worked mainly for the Boboli gardens in the service of grand duke Cosimo II. According to Baldinucci, he carved the group of the Saccomazzone after a model by Orazio Mochi. Francesco Inghirami attributes to him rightly three over life-size sculptural versions after Jacques Callot’s Caramogi. All these sculptures were made of pietra bigia between 1617 and Ferrucci’s death in 1621.

It is with these statues in Boboli that the «Villano» shares a series of significant points of comparison that would confirm its attribution to Ferrucci even if nothing were known about the commission of the sculptural group for Livorno.

In the bronze designed by Giambologna the figure rests, and he seems to meditate. Conversely, Ferrucci’s «Villano» opens his mouth as if he were in anguish and the eyes come almost out of the sockets. Such an expression is alien to the style of Giambologna but is comparable with Ferrucci’s documented pietra bigia statues in the Boboli gardens, the Saccomazzone figures and the Caramogi.

In particular the eyes of the «Villano» are reminiscent of those in the Caramogio to the right, which are of course even more expressive as the figure depends on Callot.

Similar to the above-mentioned Caramogio is also the design of the ears (figs ) and the modelling of the hair in the Peasant. The hair shares also affinities with that of the two figures in the Saccomazzone group (figs ).

Finally, in Ferrucci’s Boboli figures we find the same striations (figs ) on the garments as on the garments and the boots of the Peasant – striations that are absent in the Giambologna-inspired bronzes and that testify, in their exemplary perfection of the line, to Ferrucci’s prowess in carving.

As far as the attire of the «Villano» is concerned there is another significant point of comparison: the design of the shoes (figs ) corresponds to that of the shoes in Ferrucci’s Boboli statues.

Ferrucci’s «Villano» is not a slavish copy after Giambologna. Although the marble respects the general pose of the small bronzes, Ferrucci offers a reinterpretation of his prototype.

The main difference concerns as we have seen the head. In the marble it is energetically turned upwards. The opening of the mouth can probably be explained by this modification as an expression connected with or resulting from this movement. By all likelihood, the different position of the head and the opening of the mouth were related to the commemorative character of the statue.

There are also smaller changes, as for instance in the position of the small barrel, which prove that Ferrucci rethought the composition in terms of a large marble figure. For a marble statue, the backpack in the small bronze was obviously too large an attribute and by eliminating it the sculptor has rendered the figure slender and its outline finer.

Ferrucci has also changed the modelling of the dress. No more angular folds appear as in Susini’s small bronze.

Ferrucci’s «Villano» is a masterpiece of carving. Whereas most of the details in Ferrucci’s Boboli figures have lost their sharpness the «Villano» still preserves delicately carved passages as the two hands with most of the fingers carved all round.

Ferrucci was not an inventive genius but like Antonio Susini – assistant to Giambologna in the production of small bronzes – he was capable of rethinking the compositions of the great master in a highly original way. And like Susini he had a gift for exquisite finish. The rediscovery of the Peasant adds considerably to our understanding of the impact Giambologna had on Tuscan sculpture and makes us reconsider Ferrucci’s position in the history of Florentine sculpture around the turn of the 17th century. It is to be hoped that it would lead to a new evaluation of his personality and artistic production.

Il Villano

Il Bastione e la Statua del Villano

La Piazza del Villano si trovava tra le vie Fiume (già via del Giardino) e via Tellini. Precedentemente si chiamava p.zza dei Cavoli e successivamente p.zza della Pescheria vecchia: vi era un loggiato dove si vendeva il pesce e c’era una sorta di mercato, c’era pure il “giuoco della palla a corda” e quello del “trucco”.

1496 i Fiorentini avevano appena cacciato Piero de’Medici, figlio del Magnifico scomparso quattro anni prima…..

La Storia dal Pentagono

Piombanti nella Guida storica ed artistica della città di Livorno e dintorni: “Carlo VIII re di Francia venne in Italia con un esercito, nel 1494, per la conquista del reame di Napoli, che pretendeva gli appartenesse.

Entrato in Toscana, Pietro de’ Medici, capo della repubblica di Firenze, andò ad incontrarlo ambasciatore di pace; di proprio arbitrio gli cedè vilmente Pisa e Livorno con altre fortezze, a patto che restituisse, compita l’impresa di Napoli ; e i Francesi ai 24 novembre dell’anno stesso presero possesso del nostro castello.

Tornato il re in Francia, Firenze riebbe Livorno, pagando una somma al comandante francese; ma non poté aver Pisa, perchè lo stesso avido comandante per 12.000 scudi la consegnò ai Pisani. I quali, di fronte all’ira della fiorentina repubblica, chiesero aiuto alla lega, che si era formata contro re Carlo, a capo della quale stava Massimiliano I imperatore di Germania.

La lega, dichiarata guerra a Firenze, volle toglierle in primo luogo Livorno, ben sapendo quanto essa sel teneva carissimo. Firenze infatti aveva già fatto risarcire e fortificar le sue mura ed inalzare un bastione presso la rocca vecchia. Vedendosi ora venire addosso questa tempesta, scrisse per soccorso al re di FranCIa, mandò a Livorno rinforzi d’uomini con viveri e munizioni, e ordinò al commissario Andrea di Piero dei Pazzi che, difendesse intrepidamente il castello e alla repubblica lo conservasse. Questi munì tutti i punti con somma diligenza, e chiamò a Livorno buon numero di contadini, cui affidò la difesa del bastione. Alla metà d’ottobre 1496, Massimiliano con 7.000 uomini era a Pisa. Verso la fine dello stesso mese i nemici investivano Livorno dalla parte di terra, e da quella di mare lo bloccavano con una ventina di navi.

Il commissario e i difensori del castello, molto inferiori di numero, non si smarrirono, anzi, invocato l’aiuto del cielo, ebbero fede di poterli battere e vincere.

Pioggie dirotte impedirono per alcuni giorni agli assedianti di accostarsi al castello. Dopo le quali un primo ed un secondo assalto furono valorosamente respinti. L’armata intanto batteva Livorno e le torri di Porto pisano, tentando nello stesso tempo uno sbarco; ma il vigoroso fuoco della rocca nuova e del Marzocco, e il forte libeccio che si era levato, ne la tenevano lontana.

In questo tempo comparve la tanto desiderata; flottiglia francese, di otto navi, che portava a Livorno soldati, munizioni e viveri.

La quale ben diretta e spinta dal vento favorevole, poté entrare felicemente in porto, mentre agli sforzi delle navi nemiche non fu dato che catturarne una.

Quindi il commissario ordinò una generale sortita. Pieni i soldati di guerresco ardore, assalirono furiosamente i nemici gridando: Viva Marzocco, s. Giovanni, s. Giovanni ! In breve li sgominarono, furono per impossessarsi delle loro artiglierie, e Massimiliano stesso corse pericolo della vita.

Stanchi in fine per si fiero combattimento contro un numero troppo grande di nemici, in buon ordine si ritirarono. Indignato l’imperatore della ostinata resistenza, dette ordine che tutte le milizie assalissero il castello, mentre nello stesso tempo le navi lo avrebbero dal mare battuto.

Più ore Livorno fu il bersaglio di un fuoco terribile; ma i difensori superaron se stessi, e resero vani i più violenti sforzi dei nemici.

Era giunta intanto la notte precedente al 14 novembre, quando il libeccio, come avesse voluto por termine alla lotta disuguale, si rileva violento, spaventoso.

Mugghia il mare, i cavalloni giganteggiano, l’armata dei nemici viene sbaragliata. Alcune navi furon gettate a traverso; le rimaste, mezzo disarmate e guaste, a stento ripararono a Pisa.

Scoraggiato e indispettito Massimiliano, perchè, fallito l’assalto da terra, vide anco l’armata ridotta all’impotenza, tolse l’assedio, e, bruciati gli accampamenti, Livorno fu libero.

Feste straordinarie si fecero qui e a Firenze; e al castello nostro rimase e rimarrà imperitura la gloria di aver vinto un imperatore germanico e i suoi alleati

La fiorentina repubblica in attestato di riconoscenza ai contadini, che si erano bravamente battuti, fece porre sulla pubblica fonte di Livorno la statua di un giovane villano appoggiato ad un bastone, con ai piedi un cane, simbolo di fedeltà, che poi ebbe nome la fonte del villanoi volontari accorsi sono chiamati “villani” nel senso di villici, abitanti della “villa” della campagna.Per dare un attestato di riconoscenza ai valorosi villici livornesi che avevano difeso il Castello di Livorno assediato dall’Imperatore Massimiliano nel novembre del 1496, la Repubblica Fiorentina ordinò che sulla piazza della pescheria vecchia, che fu poi detta del Villano, fosse innalzata una fontana con sopra una statua rappresentante un giovane contadino appoggiato ad un bastone con ai piedi un cane, simbolo di fedeltà. La statua, assai pregevole, era di pietra di macigno ed era stata scolpita da Romolo del Tadda.

Giovanni Wiquel nel Dizionario di persone e cose livornesi così scrive: ”Nel 1873 la fontana era ancora dove fu originariamente messa ma senza la statua che, danneggiata, fu tolta, ma non si sa quando;. nella Pinacoteca Comunale vi è un quadro che ci serba l’immagine dell’antica statua”.Nel 1956, ricorrendo il 350° anniversario della elevazione di Livorno al rango di città (19 marzo 1606), l’Amministrazione Comunale deliberò che fosse realizzata una nuova statua del “Villano” e del suo fedele cane. L’incarico fu affidato agli artisti Vitaliano De Angelis e Giulio Guíggi, i quali, ispirandosi all’opera originale, realizzarono l’attuale statua del Villano. Dal Pentagono

prima statua dedicata a Guerrino della fonte di Santo Stefano o da Montenero,

foto di archivio: il Villano originale di Romolo del Tadda, scultore fiorentino attivo fra il Cinquecento e il primo Seicento specializzato nel lavorare la pietra, autore di qualche statua da giardino a Boboli….

Si tratta di una tela di anonimo del Seicento, che dovrebbe essere da qualche parte proprio in Comune o nel museo comunale, e di un disegno di Padre Santelli, dal manoscritto conservato alla Labronica. L’originale si deteriorò e sparì forse nel Settecento. (confr. Piombanti, nota a pag. 17)

Prima che Giulio Guiggi e Vitaliano De Angelis eseguissero nel 1956 il Villano in bronzo che ancora vediamo, per il trecentenario di Livorno città, nel 1906, fu eseguita dallo scultore Lorenzo Gori una statua in gesso che non fu mai fusa in bronzo e si deteriorò presto. La cosa di rilievo è che fu posta sul basamento di pietra serena (?) della statua antica, ancora in collocazione originale e fino ad allora sopravvissuto all’opera di Romolo del Tadda.

Nel 1896 in occasione del 350° anniversario della Difesa di Livorno fu scoperta una lapide. Fatto che evidenzia come fino ad allora quella data fosse legata ad un evento festeggiato e sentito, poi complice forse l’implicito riferimento al periodo Repubblicano fiorentino e Toscano e i miti del Risorgimento e della della difesa contro gli austriaci ne offuscarono il destino.

Sulla distruzione del la statua ggesso …

GAZZETTA LIVORNESE, 14 marzo 1906

La statua del Villano.

“Ieri nelle ore pomeridiane, tra una folla di curiosi, fu posta sull’antica fonte, in piazza della Vecchia Pescheria, la statua del Villano. Fu eseguita in gesso, o meglio in pochi giorni improvvisata, in un magazzino di via S. Antonio per conto del Comitato popolare.

Da quanto ci viene riferito, la statua è piaciuta a moltissime persone che l’hanno in questi giorni visitata, mentre l’amico Gori, coadiuvato dal Salvadori e dal Prof. Crivellucci, stava per dare gli ultimi tocchi.

La statua attualmente è coperta; oggi è stata scoperta per farne la fotografia.”

I Bastioni di Cosimo I°

Explore Josse Sébastien Van den Abeele

RKD

Benvenuti in Livorno3d

Minisito storicartofotografico dedicato alla Livorno scomparsa